Green books for boys, pink books for girls… these traditional French stereotypes have enchanted generations of young readers. Yet there is another colour to add to this palette: blue.

“Blue books” have long disappeared from French bookshops and libraries, but they nevertheless played an important role in the history of the printed word in France. Indeed, these “blue books” are none other than the ancestor of our modern-day “pocket book”. And they were invented in Troyes!

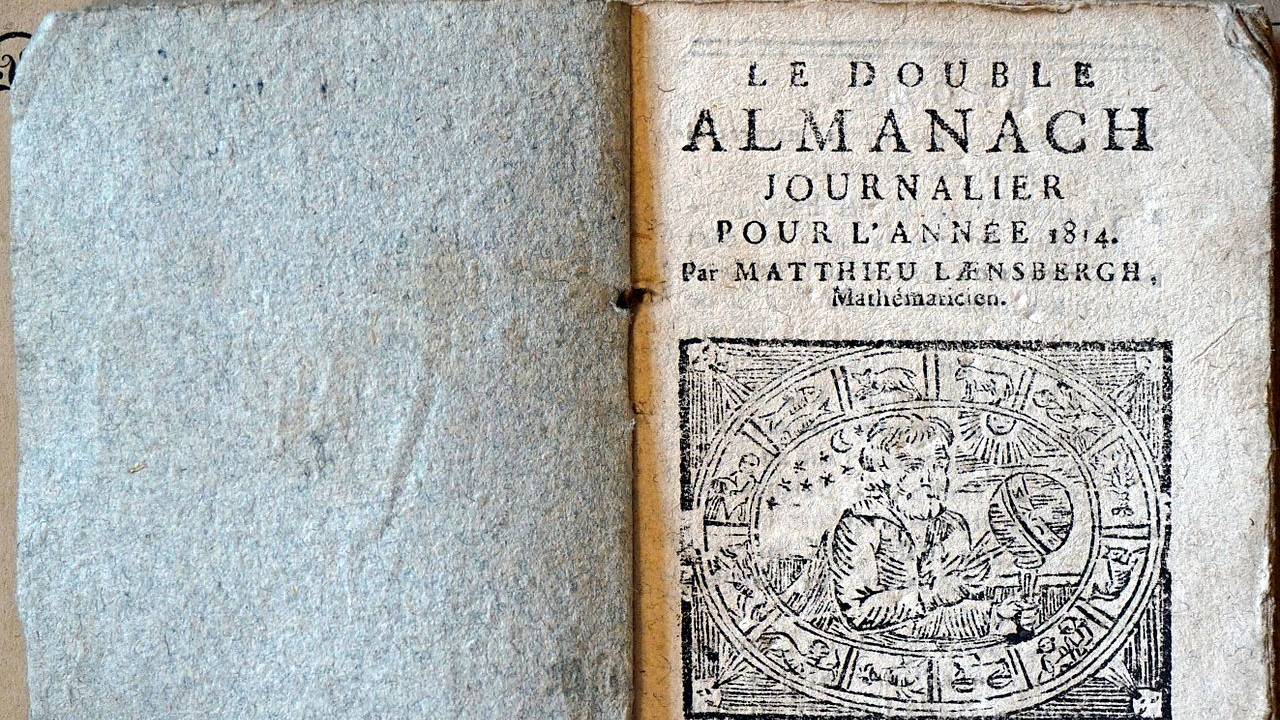

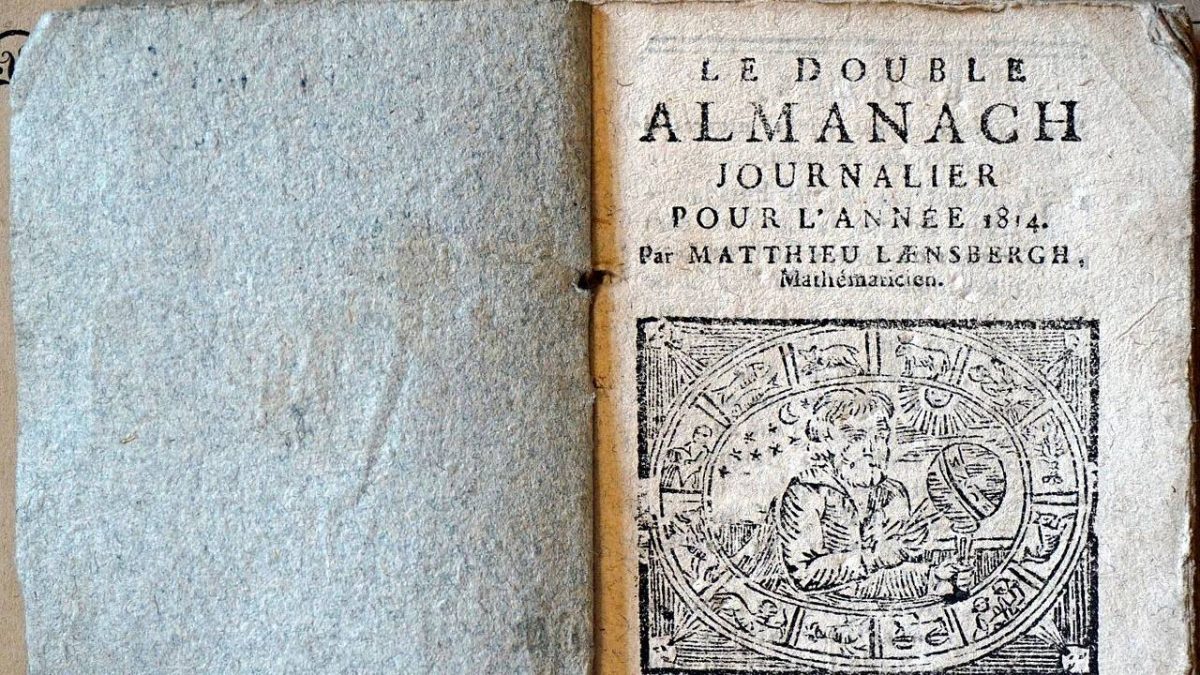

The “blue book” emerged in Troyes in the early 17th century, the invention of a Troyen printer. He decided to “recycle” books that had already been published. These new editions were re-written, abridged versions designed for the general public. These were the “low-cost” books of their era: fewer pages, cheap paper, poor-quality printing, rough cutting, huge print runs, regurgitated illustrations and texts filled with misprints and typos.

Yet the format was revolutionary, with these little books measuring just 12 x 7 cm or 22 x 15 cm. They were sold at an extremely cheap price, and the distribution process helped to bring reading to the masses across France, with pedlars selling these “blue books” at town and village fairs and markets. They were known as “blue books” because of the colour of their covers, made from paper that had previously been used to package sugarloaf.

The “blue book” distribution system also gave rise to the term «colportage». If the train had existed at the time, it might also have been known as “station literature”.

This format enjoyed immense success, and the Troyen model was copied by many other towns and cities. In the 19th century, the catalogue contained around 4,500 titles, including several hundred “best sellers”. Traditionally, the books were read in groups during the evening and at night.

The “blue book” collection featured literature of all varieties, from chivalry novels to the lives of saints, Bible stories to love stories, fairy tales to recipe books, etiquette guides to astrological calendars, etc.

From this midst of this jumble emerged one genre that would go on to become a huge hit: the almanac, that great populariser of knowledge. In short,

this new format was instructive, informative, entertaining and inspiring. The “blue books” played an important role in the transmission of popular culture, and in developing literacy throughout the population.

Troyes was the father of the paper industry, a pioneer in the printing sector and an early publishing giant. This fact is reflected in its Media Library, which still holds more than 3,000 of these famous “blue books” – the largest collection of its kind in France. The Media Library even re-published three “blue books” in 1999.